Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro is sowing doubt about the validity of the country’s electronic voting system ahead of the first round of elections, ratcheting up fears that he may refuse to accept defeat if the vote doesn’t go his way — much like his political idol, former U.S. President Donald Trump.

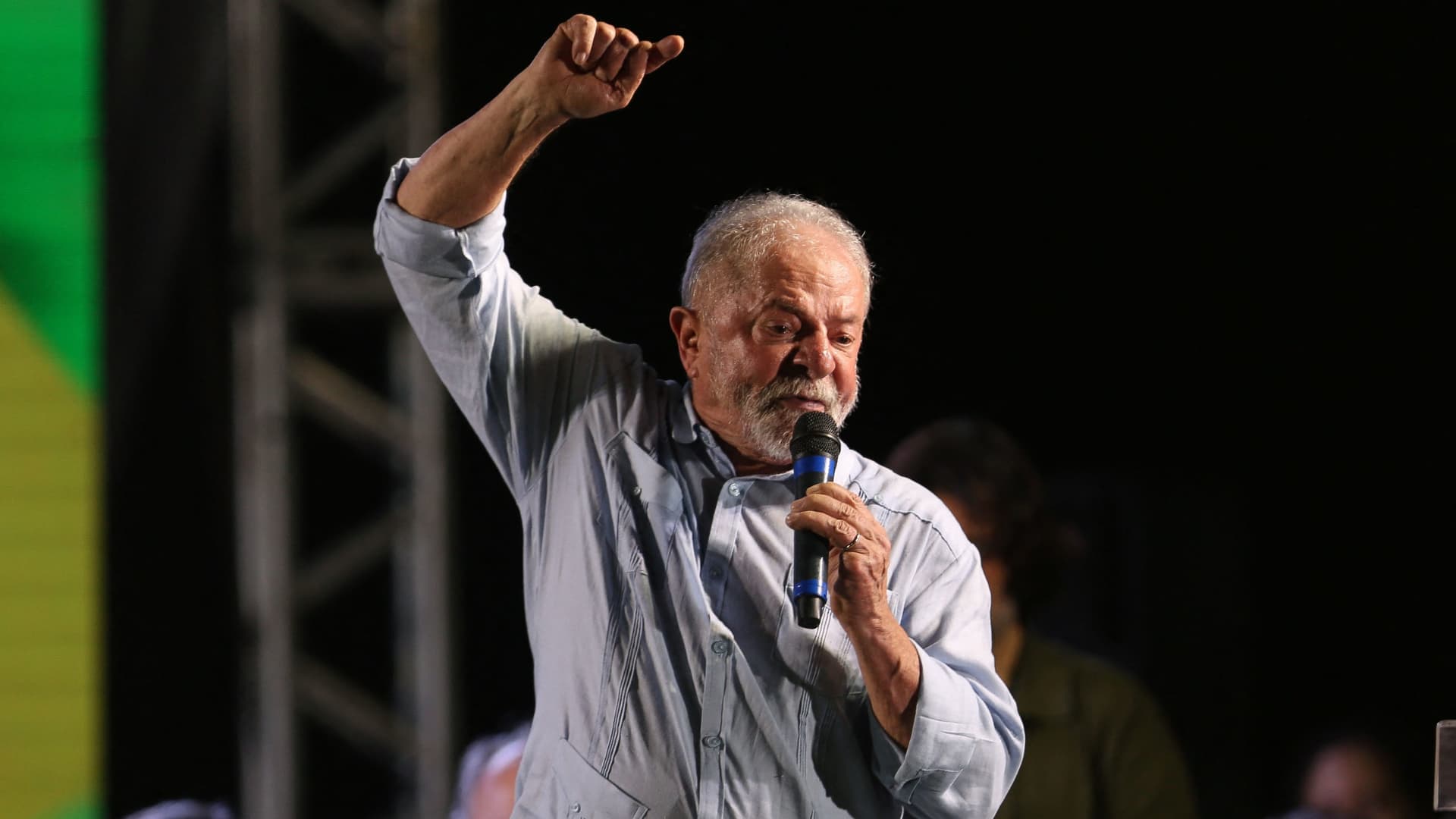

The first round of Brazil’s presidential elections, scheduled for Oct. 2, sees Bolsonaro come up against his political nemesis and former leftist president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in what has become Brazil’s most polarized race in decades.

Da Silva has consistently been polling comfortably ahead of the far-right former army captain in both the first round and an expected run-off, although some opinion polls have shown the incumbent narrowing the deficit in recent days.

“This trend of Bolsonaro narrowing the distance from Lula will keep going in the next few weeks probably,” Adriano Laureno, political and economic analyst at consultancy Prospectiva in Sao Paolo, Brazil, told CNBC via telephone.

Bolsonaro, who is running under the banner of the Liberal Party, has previously said he would be prepared to accept the result of the election whoever wins — but not if there is any indication of voter fraud.

Since coming to power in early 2019, the scandal-hit president has faced widespread criticism for his response to the coronavirus pandemic and his environmental track record, while also facing numerous calls for impeachment.

Political analysts said Bolsonaro’s criticism of the country’s respected electronic electoral system, which has never detected significant fraud, was likely designed to mobilize his supporters ahead of the first round of voting.

“Bolsonaro’s rhetoric has been that he will accept the result but only if the result is clean and transparent. So, what he is really saying is that he doesn’t rely on the electoral system, he doesn’t rely on the Supreme Court and as a result, he does not seem in the mood of relying on the electoral system as a whole,” Laureno said.

Indeed, even after winning the 2018 election after a second-round run-off, Bolsonaro vociferously made baseless allegations of voter fraud and suggested he should have won outright in the first round.

“Even an election that he won, he questions [the result]. So, imagine what will happen if he loses,” Laureno said.

Bolsonaro has long embraced comparisons to Trump, being dubbed the “Trump of the Tropics” by the country’s media. And it is thought he may now be drawing from the former U.S. president’s playbook in seeking to call into question the democratic process.

‘Climate of hatred’

A return to office for Da Silva, who led Latin America’s biggest country from 2003 to 2010, would mark an extraordinary political comeback.

The former metalworker was jailed in 2017 in a sweeping graft investigation that put dozens of the country’s political and business elites in prison. Da Silva was released in Nov. 2019 and his criminal convictions were later annulled, paving the way for him to seek a return to the presidency.

Ana Mauad, assistant professor of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogota, Colombia, told CNBC that there are expectations among Lula’s supporters and within his Workers’ Party that he could win in the first round, although she does not believe this will happen.

Asked whether she then expected Da Silva to secure victory in the second round, Mauad replied, “Yes, definitely — if we have a second round. And I am more of a pessimist in that sense because Bolsonaro is calling his supporters and increasing the tension between supporters from both candidates.”

In one of the latest instances of the mounting political tensions in Brazil, authorities reported last week that a Bolsonaro supporter stabbed to death Benedito Cardoso dos Santos, a 42-year-old backer of Da Silva. The incident occurred in Mato Grosso, a large state in west-central Brazil.

Commenting on the violence, Da Silva told reporters in Rio de Janeiro on Friday that there was a “climate of hatred in the electoral process which is completely abnormal.”

A new pink tide?

Brazil’s presidential elections come at a time when Latin America’s new so-called “pink tide” appears to be gathering pace.

Left-of-center candidates have won elections in Mexico, Argentina, Bolivia, Peru and Honduras in recent years, while leftist leader Gabriel Boric secured a historic victory in Chile last year, and Gustavo Petro became Colombia’s first leftist leader in June. The growing leftist bloc echoes a similar regional political shift seen two decades earlier.

“This is a Latin American tradition, right? We had this left-wing wave back in the 2000s when Lula was first president in Brazil in 2003,” Mauad said. “But what is happening right now is a very different moment for Latin America.”

Mauad said it was difficult to call Latin America’s leftist resurgence a new pink tide because the new group of presidents sweeping to power — inspired by Chile’s Boric — place climate policies and gender issues at the forefront of their campaigns.

“That marks not only a generational difference but also the perspective of what it means to be left and progressive in Latin America right now,” Mauad said.

“We had a more organic left if the first wave in the 2000s and 2010 because most of them were these charismatic leaders. They were this left based on ideas of industrialization and development of the region,” she added.

“Boric represents this more progressive left in the region. I think Lula right now and some parts of his party are saying, ‘look we need to be closer to Boric and not to Petro or [Argentinian President] Alberto [Fernandez].'”

The fate of the Amazon

Alongside key electoral issues such as rising inflation and the health of Latin America’s largest economy, the fate of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is in sharp focus. That’s because deforestation in the rainforest, often referred to as the “lungs of the Earth,” has skyrocketed under Bolsonaro’s presidency.

Deforestation was reported to have broken all records in the first six months of 2022 amid a dramatic uptick in Amazon destruction and attacks on Indigenous communities.

Da Silva has pledged a major crackdown on Amazon crime if elected, while Bolsonaro — despite widespread criticism for his destructive policies — has outlined proposals to halt deforestation in the rainforest.

“I think a major part of the debate is about the credibility of the candidate’s management of society. The economy in Brazil is really starting to struggle now in the aftermath of the pandemic. Lula, of course, has a good track record in that respect and Bolsonaro much less so,” Marieke Riethof, senior lecturer in Latin American Politics at the University of Liverpool, U.K., told CNBC via telephone.

“I think among the lower income voters, the candidate’s ability to offer some kind of social policies and financial compensation is also going to be really important,” Riethof said.

“Bolsonaro offered compensation during the pandemic, but the question is would he continue doing that? Or are voters more likely to get it from Lula?”