Why Canadian oil is sold to the U.S. at a ‘discount’ and have tariffs made things worse?

Canada supplies around four million barrels per day to the U.S., roughly half that country’s total crude imports

Article content

Canadian oil prices have been unexpectedly resilient so far this year despite escalating trade tensions with the United States, with the discount on Canada’s benchmark heavy oil, Western Canadian Select (WCS), shrinking last week to its narrowest gap since 2020.

Article content

Article content

U.S. President Donald Trump’s repeated threats to impose tariffs on Canada since his re-election last November initially put pressure on Canadian crude prices. But since early March, when he exempted Canadian goods covered under the Canada-United-States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), and amid fresh U.S. sanctions on rival heavy oil exporter Venezuela, demand for Canadian heavy crude has been particularly strong.

Advertisement 2

Story continues below

Article content

Still, on the eve of Trump’s planned reveal of reciprocal tariffs against its global trading partners, there are still plenty of questions about how U.S. tariffs could impact cross-border energy trade.

Here, we take a closer look at the pricing of Canada’s key benchmark crude and how tariffs are influencing prices for Canada’s largest export product to the U.S.

What is Western Canadian Select?

WCS is the main benchmark crude for Western Canada and the definitive price marker for the heavy barrels produced from the vast oilsands deposits in northern Alberta.

It is considered a heavy, sour crude oil and typically trades at a lower price than light, sweet crude types that are easier and cheaper to refine, such as West Texas Intermediate (WTI).

WCS was launched in the early 2000s by a handful of large oil companies in Western Canada that were trying to sell more heavy barrels to Midwest refineries. At the time, producers were churning out dozens of different streams of crude oil of varying quality.

“They had all these relatively small streams of heavy crude and it was very difficult to market those streams,” Jeff Kralowetz, vice-president of business development for commodity research firm Argus Media Ltd., said.

Advertisement 3

Story continues below

Article content

The producers got together and decided to blend around 20 different grades of conventional heavy oil, synthetic crude and diluted bitumen from the oilsands at the largest oil storage hub in Canada in Hardisty, Alta., he said. The barrel they came up with closely resembles Mexico’s heavy crude benchmark, Maya.

“Which was important because at the time, Mexican Maya crude was one of the main heavy crudes available at the Gulf Coast,” Kralowetz said. “They wanted to compete head-to-head with it, so they created a blend that looked a lot like it.”

Canada’s push for U.S. market share spectacularly paid off. U.S. imports of Canadian crude have doubled since 2009, while imports from Mexico and Venezuela have declined.

Canada now supplies around four million barrels per day to the U.S., roughly half that country’s total crude imports.

Why is the U.S. able to buy Canadian oil at a “discount”?

You’ll often hear federal Conservatives and politicians in Alberta complain that Canadian oil is being sold to the U.S. at a discount, fetching lower returns than it could get on global markets. That isn’t wrong, but it’s not the whole story.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Story continues below

Article content

Heavy oil, such as WCS, which also has a high sulphur content, is considered a lower-quality crude and will always trade at a discount to lighter grades since it requires more costly refining and processing to produce valuable end products like gasoline, diesel and jet fuel.

There is, however, a profitable upside for refiners that invest in the necessary upgrades to handle heavy sour crudes since heavy feedstocks are cheaper and can yield a greater range of refined products.

Canada’s barrels are also largely landlocked, with most production being far from North America’s key transport hubs and refineries, and its lower price reflects higher transportation costs and Western Canada’s limited access to global markets.

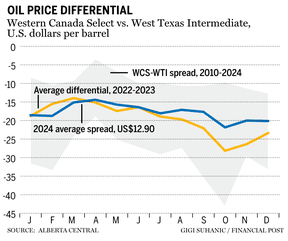

As a result, WCS trades at a lower price than WTI and that difference is known as the WCS-WTI differential.

There have also been painful periods for the Canadian oilpatch when production has outpaced available pipeline capacity, resulting in oil supply gluts that have cratered prices.

Pipeline bottlenecks in 2018 led to the WCS-WTI differential exploding to more than US$40 per barrel, prompting the Alberta government to impose a curtailment order on production to bolster prices.

Advertisement 5

Story continues below

Article content

On Canada’s side of the border, blowouts in the differential result in a painful contraction of revenues and economic activity, while American refiners enjoy windfall profits as their margins are boosted by dramatically cheaper crude inputs.

Currently, there isn’t a shortage of takeaway capacity in the Canadian oilpatch due to key export pipeline expansions completed in recent years, such as the Enbridge Line 3 replacement project in 2021 and the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion (TMX) in 2024.

Heading into the U.S. election last November, Canadian oil producers were enjoying the novel sensation of having plenty of pipeline capacity and consistently narrower discounts on their barrels coinciding with the start-up of TMX last May.

Canada’s only direct outlet to global markets outside the U.S., the TMX expansion more than doubled non-U.S. oil exports in the second half of 2024.

That has helped shrink the spread between WCS and WTI, which has consistently hovered between US$10 and US$15 per barrel in the months following TMX’s start-up after years of it averaging more than US$18.

Advertisement 6

Story continues below

Article content

“When you only have one buyer, that buyer has a lot of leverage over your price,” Kralowetz said. “The completion of TMX in May was a big step. You automatically had an improvement or a narrowing of the discount.”

How are U.S. tariffs impacting the price of WCS?

Oil market analyst Rory Johnston said the best way to spot the impact of U.S. tariffs on Canadian crude prices is not by looking at the relatively tight WCS-WTI differential, but at the spread between the price of a barrel of WCS in Hardisty, Alta., versus the price WCS fetches once it reaches Houston.

The Hardisty-Houston price gap reflects the transportation costs associated with bringing a barrel of WCS from Alberta to complex refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast, and it ranged between US$6 and US$8 per barrel in the months before Trump’s election, according to a recent analysis by Johnston in Commodity Context.

Anything in excess of that geography-related differential baseline since the U.S. election can reasonably be chalked up to a tariff-related penalty on Canadian barrels, Johnston said.

The tariff penalty started rising after a newly re-elected Trump began threatening tariffs on Canada and Mexico on social media, Johnston said, and then exploded in January.

Advertisement 7

Story continues below

Article content

“We got the biggest run-up initially following Alberta Premier Daniel Smith’s visit to Mar-a-Lago the week before inauguration, when she came out and basically said, ‘Guys, (tariffs) are happening and crude is not going to get exempted,’” Johnston said, noting the WCS Hardisty-Houston differential reached US$12.40 per barrel at market close on Jan. 31, nearly US$5 per barrel in excess of the pre-election baseline. “At that stage, the market was essentially pricing the risk of a 25 per cent tariff.”

But Trump’s subsequent decision to reduce tariffs on Canadian crude to 10 per cent, as well as his postponements and vacillations over the implementation of tariffs since then, has recently led to a collapse in the tariff penalty as markets seem to largely be discounting the risk of tariffs being applied to Canadian crude at all.

“After that (CUSMA) exemption a couple weeks ago, that’s when the market really started to just discount the risk of tariffs on Canadian crude in total, so now we’re basically at almost zero risk,” Johnston said.

The overall WCS-WTI discount fell below US$10 a barrel last week, the narrowest margin since 2020.

Advertisement 8

Story continues below

Article content

Recommended from Editorial

Markets may be reflecting a belief that Canadian oil exports, so deeply integrated into the U.S. economy, are likely to continue to be exempt from tariffs, Johnston said.

But that may be an overcorrection, he added, given the current state of tensions between Canada and the U.S. and Trump’s looming reciprocal tariffs.

“I would personally say the risk remains higher than zero per cent,” he said. “But it also confirms this initial prior thought everyone had going into this that maybe Trump will tariff lumber or autos or something, but he’s not going to tariff crude. That’s crazy.”

• Email: mpotkins@postmedia.com

X: @mpotkins

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content

Comments