Boeing Max Declared Safe to Fly by Europe’s Aviation Regulator

(Bloomberg) — Europe’s top aviation regulator said he’s satisfied that changes to Boeing Co.’s 737 Max have made the plane safe enough to return to the region’s skies before 2020 is out, even as a further upgrade his agency demanded won’t be ready for up to two years.

After test flights conducted in September, EASA is performing final document reviews ahead of a draft airworthiness directive it expects to issue next month, said Patrick Ky, executive director of the European Union Aviation Safety Agency.

That will be followed by four weeks of public comment, while the development of a so-called synthetic sensor to add redundancy will take 20 to 24 months, he said. The software-based solution will be required on the larger Max 10 variant before its debut targeted for 2022, and retrofitted onto other versions.

“Our analysis is showing that this is safe, and the level of safety reached is high enough for us,” Ky said in an interview. “What we discussed with Boeing is the fact that with the third sensor, we could reach even higher safety levels.”

The comments mark the firmest European endorsement yet of Boeing’s goal to return its beleaguered workhorse to service by year-end, following numerous delays and setbacks. The Max, the latest version of the venerable 737 narrow-body, was grounded in March 2019 in the wake of two accidents that took 346 lives, setting into motion a crisis that’s cost Boeing billions of dollars and the then-CEO his job.

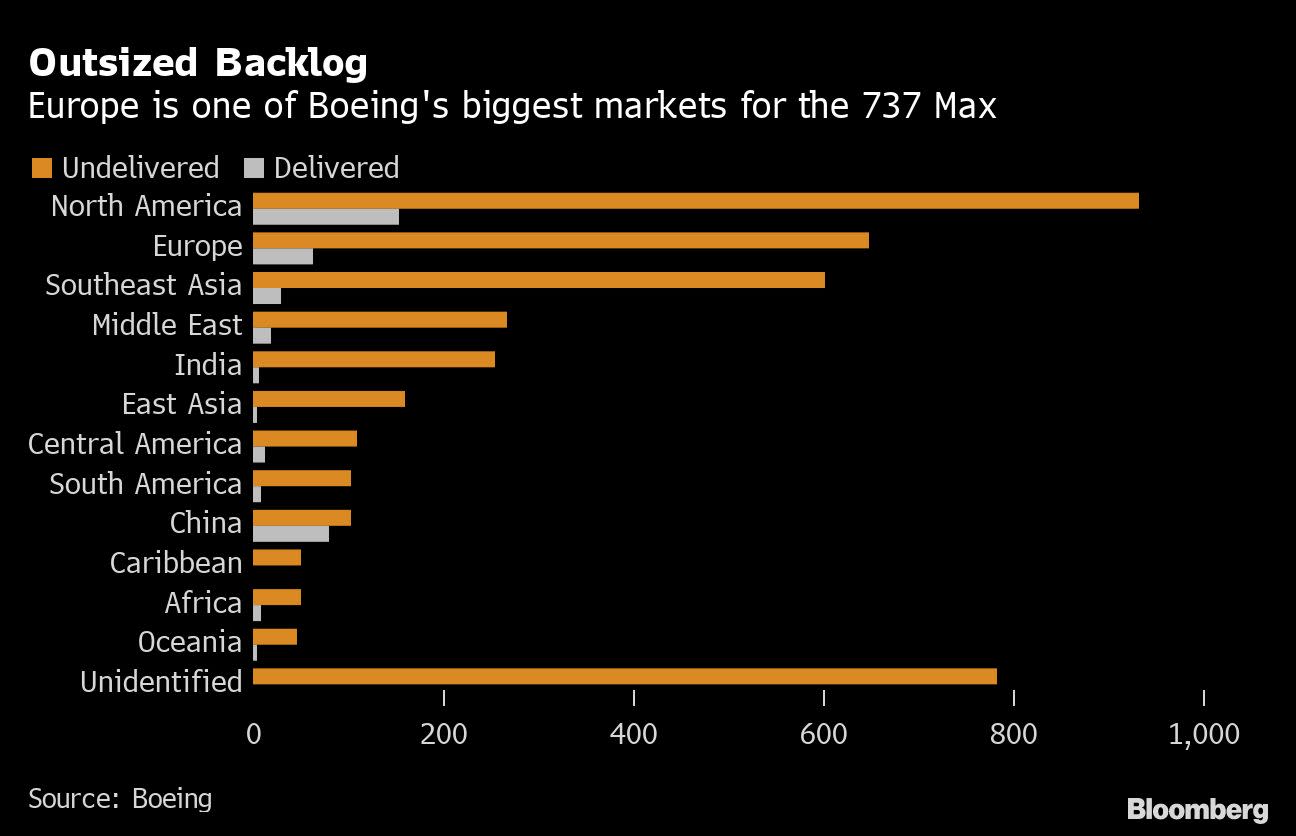

While the Federal Aviation Administration, Boeing’s main regulator, is preparing to clear the plane’s return, EASA’s views carry outsize weight, especially in light of flaws in the original certification process that dented the U.S. regulator’s sterling reputation.

Ky said the synthetic sensor would simplify the job of pilots when one or both of the mechanical angle-of-attack sensors on the Max fails. The device, which monitors whether a plane is pointed up or down relative to the oncoming air, malfunctioned in both crashes — the first off the coast of Indonesia in October 2018 and the second one, five months later, in Ethiopia.

“We think that it is overall a good development which will increase the level of safety,” Ky said. “It’s not available now and it will be available at the same time as the Max 10 is expected to be certified.”

New Beginning

The Max episode strained the rapport between the FAA and global aviation authorities including EASA which acted faster to bench the jet and have made demands that go beyond U.S. requirements to clear its return. Ky said the relationship between the European agency, home regulator to Boeing rival Airbus SE, and its U.S. counterpart needs to be rebuilt in a way that enhances safety while not slowing down progress.

“For the FAA, the Max accident has been a tragedy,” he said. “In terms of the way in which they perceive their own roles, the way they were attacked by different stakeholders in the U.S., the way they have been criticized, it must have been extremely difficult.”

Read more:

FAA Chief Likes Revised 737 After Flight, But Review Continues

Boeing Tempers Hoopla on Max’s Return After Crisis ‘Dug a Hole’

Boeing 737 Max Return Outside U.S. Seen Slowed by Regulators

FAA’s Oversight of Boeing 737 Max Jet Slammed by Lawmakers

The FAA’s relationship with Boeing has also changed, after the planemaker was accused of hiding changes that magnified the differences between the Max and earlier 737 models in order to reduce costs and minimize training requirements.

“At the end of the day,” Ky said, “we have a lot of respect for the technical expertise at the FAA, we have a lot of respect for our colleagues and I’d like to believe it is the same on their side. That is the real important foundation for the relationship to grow again, it has to be based on respect.”

Another question mark for the Max is China, where aircraft demand surged leading up to this year’s coronavirus pandemic. China has participated in some of the Max reviews but hasn’t been involved in the flight testing that includes regulators from Canada and Brazil along with the FAA and EASA, Ky said. “I honestly don’t know where they are” with their evaluation, he said.

New Challenges

As the Max saga winds down, EASA is working with other regulators to apply the lessons learned to future certifications. One area has to do with evaluating derivative models like the Max that bolt modern technology onto older platforms. The challenge is finding the right balance and making sure pilots have the knowledge they need to fly the planes safely, he said.

One coming derivative is Boeing’s 777X, the next version of its 25-year-old wide-body with folding wings. Like many Boeing planes, it has two angle-of-attack sensors (Airbus jets have three or more). When discussing the Max, Ky said that the important question when one of two AOA sensors fails was its impact on the safety of the plane.

While the 777X doesn’t feature the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System that played a role in the Max crashes, Ky said EASA will closely study the new 777’s flight control systems and analyze any potential points of failure as part of its review.

As to whether this would slow the European approval process for the wide-body: “It depends a lot on whether Boeing is able to give us the right solutions and the right analysis on the risk assessment,” he said. “There may be other problems; we are really looking into this new aircraft and we are making sure that ours and Boeing’s safety assessment is done properly and doesn’t leave any questions unanswered.”

Hydrogen, Drones

Here are some of Ky’s comments on other topics including drones, new software and technologies such as hydrogen propulsion:

EASA won’t ask for changes on previous generations of the Boeing 737 jet, such as the NG, unless they are relevant. So far, none of the changes that regulators have asked for on the Max applyThe European agency is building up expertise in future technologies, software and propulsion systems. Certification of drones is a challenge, as a lot of manufacturers come from non-aviation backgrounds, and have “a completely different process of development.”Some aviation software is developed using safety standards dating from the 1980s. Non-aviation companies working on autonomous flight, for example, may have an approach “that actually builds more robust software than ones that we certify” using the existing process. EASA is investing to build regulators’ competence in evaluating technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learningEASA is starting to work with the European Space Agency to build know-how around hydrogen propulsion, which is used in spacecraft. “Technically, from a pure propulsion standpoint, it’s not that difficult. What is much more difficult is the storage of the fuel on board that aircraft”

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

Subscribe now to stay ahead with the most trusted business news source.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.