It really is different this time — a new era for stocks is just getting started

What if the real lesson for investors who study financial-market history is that the future will be unlike the past? Financial markets periodically undergo profound sea changes that have little similarity to what came before. This means that history tells us little other than that the future is unknowable.

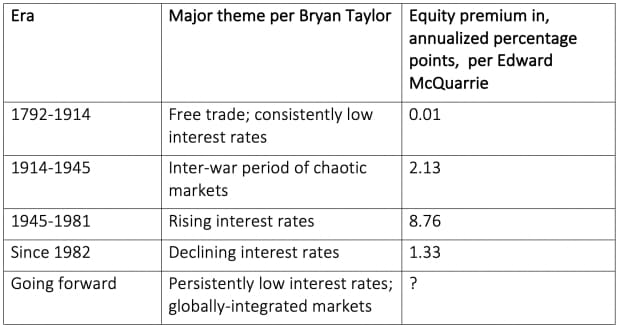

Bryan Taylor, chief economist at Global Financial Data, believes we currently are undergoing another of these sea changes. The table below summarizes the previous eras in U.S. market history back to 1792, as Taylor laid them out in an interview.

The table also reports for each era the amount by which stocks beat bonds — the so-called equity premium. The equity premium data are from a new database compiled by Edward McQuarrie, a professor emeritus at the Leavey School of Business at Santa Clara (Calif.) University. The data for the period from 1982 ends in 2019.

Taylor’s best guess is that an era of persistently low interest rates is just getting started. He said that it would be unrealistic to expect anything like the declining interest-rate era from 1982, since interest rates are already so low. While an era of rising interest rates is possible, this also seems unlikely in light of the Federal Reserve’s stated intentions. The chaotic markets of the 1914-1945 period that included two world wars also seem an unlikely guide for the future, as does the 1792-1914 period in which the U.S. transformed into an industrialized economy.

This is why Taylor believes investors are entering uncharted territory. He predicts that the equity premium going forward will be small — around 3%. If so, stocks in this unfolding era will produce returns that are, at best, mediocre.

Recall that bonds’ long-term returns are highly correlated with their beginning yields. For example, the 10-year U.S. Treasury TMUBMUSD10Y,

The challenge for investors

Taylor stresses that his 3% equity premium estimate “is only a dart-throwing guess.” That perhaps is the more important point of this discussion: a guess is the best anyone can do. Based on the past four decades, for instance, you can project an equity premium of 1.33 annualized percentage points. You can project a higher equity premium if the data analysis goes back to World War II, or a much lower premium if you start the analysis from 1792.

Yet if the financial markets instead are marked by eras that bear little resemblance to each other, then analyzing more history doesn’t necessarily produce greater insight. McQuarrie makes this point: “Mashing apples and oranges together cannot give a better grasp of how different fruits taste.”

The bottom line? Humility is a virtue. Those who project confidence because of how much history they’ve included in their models are like those who are often wrong but never in doubt.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

Plus: Dow 37,000? It’s possible if U.S. stocks stage an ‘average’ summer rally