Taper tantrum? Only if somebody wakes the U.S. bond market

Quiet, please, the bond market is sleeping.

In February and March , as the U.S. economy began to recover from the coronavirus pandemic, a selloff in U.S. Treasurys sent yields up sharply, with the 10-year benchmark BX:TMUBMUSD10Y coming within a whisker of 1.8%. Partly as a result investors began to rotate away from technology and other growth stocks that are sensitive to higher interest rates which had performed well during the pandemic, limiting further gains in the major stock indexes.

Since then the bond market has been subdued, with yields falling back below 1.6% even as fears of a surge in inflation have mounted as businesses have reopened and consumer demand has ramped up. The market calm seems to fly in the face of talk of a repeat of the 2013-14 “taper tantrum” that left bond traders with psychological scars after yields rose sharply when the Federal Reserve began to slow its purchase of bonds as the economy recovered from the 2008 financial crisis.

“We’ve had a big move already,” said Kathy Jones, chief fixed-income strategist at the Schwab Center for Financial Research, in a phone interview, referring to the rise of over one percentage point in the 10-year yield from just above 0.5% last summer. And that move occurred without the Federal Reserve fiddling with its $120 billion-a-month bond purchase program, she noted.

Related: Why the bond market might not suffer another taper tantrum when the Fed signals it’s ready to move

Jones and other bond watchers are skeptical that a taper-tantrum rerun is in the cards. The original event occurred after then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke told lawmakers in May 2013 that the central bank could begin to pare back the bond purchases implemented in the 2007-09 recession if the economy continued to improve.

Kit Juckes, global macro strategist at Société Générale, argued in a May 27 note that the rise in yields off the pandemic lows of 2020 had already delivered something roughly equivalent to the 2013-14 episode.

U.S. 10-year yields “rose from a low of 1.4% in 2012, to 3% during their tantrum. In this cycle, the rise has been from 0.5% to a high just below 1.8%. That’s comparable in relative terms. The eventual peak in U.S. yields in 2018 was 3.25%. Can’t we accept that the taper tantrum has already happened?” he wrote.

As implied by Juckes’s reference to the 2018 peak, that doesn’t mean yields can’t rise above their March highs, analysts said. Indeed, Jones looks for the 10-year yield to rise toward 2% by year-end. But it does argue against the sort of disorderly selloff that can send ripples through financial markets.

Why do memories of the taper tantrum hold sway over investors?

“I think the key there is that it caught everyone by surprise,” Jones said.

In 2013, the market not only wasn’t prepared for the Fed to consider slowing purchases, investors had never experienced a tapering of asset purchases, she said. Now, investors have experienced not only a tapering, but a reduction in the size of the Fed balance sheet in 2018 that wasn’t traumatic.

See: Is the Fed tightening cycle already happening?

What’s more, when the Fed does signal it’s ready to taper, it’s not going to catch anyone by surprise, Jones said.

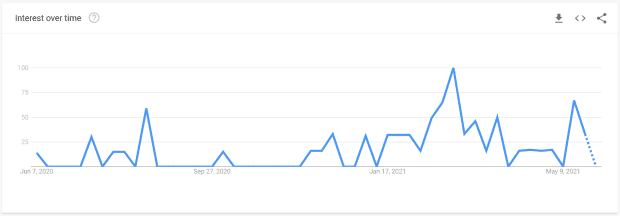

Searches for ‘taper tantrum’

Google Trends

As the chart above shows, searches for “taper tantrum” via Google have started to slow after spiking last month. And bond yields have come down even as Federal Reserve officials have moved from insisting it was too early to contemplate even thinking about slowing asset purchases to acknowledging that such discussions may be on the agenda sooner rather than later.

Treasury yields fell Friday after a somewhat disappointing — by pandemic-recovery standards — May jobs report showed the economy produced 559,000 new jobs last month and as investors brushed off a pickup in wage growth, which clocked in at 0.5% month over month and 2% year over year. Rising wages amid signs of labor shortages can contribute to inflation fears.

Read: Record job openings and higher pay still not enough to get Americans back to work

The week ahead may offer a further test of bond investor tolerance. The May consumer-price index, due Thursday morning, is the highlight of the economic calendar. A hotter-than-expected 0.8% jump in the April CPI reading last month, translating into a 4.2% year-over-year rise, appeared to briefly revive taper-tantrum fears.

Economists at the Institute of International Finance, meanwhile, said the 10-year’s sideways yield action over the last two months is likely a product of the Fed’s average-inflation targeting stance, in which it has vowed to allow inflation to run above its 2% target for a spell to make up for past undershoots and allow the labor market to fully heal.

“It is notable how few hikes are priced into front-end interest rates compared to the tantrum in 2013, even as rapid progress on vaccinations and prospects of a rapid recovery would warrant such a risk premium,” they said, in a June 3 note.

“We think this is a genuine obstacle to 10-year yield going higher and it will take strong data — tangible evidence of the rebound — to break this stalemate,” they wrote.

Speculation around the pace of asset purchases, meanwhile, isn’t confined to Fed watchers. European Central Bank policy makers meet Thursday. The goal amid a brightening economic outlook and rising eurozone inflation will be to “avoid any taper talk,” wrote analysts at ING.

Others expect the ECB to take action. Policy makers are likely to announce a slowdown in purchases of bonds under the ECB’s pandemic emergency purchase program, or PEPP, which currently run at around 20 billion euros ($24.3 billion) a week, while “sending a dovish medium-term message,” wrote Luigi Speranza, chief global economist at BNP Paribas, in a note.

Such a move would allow yields to rise in line with an improving economic outlook, while leaving monetary and financial conditions largely unchanged.

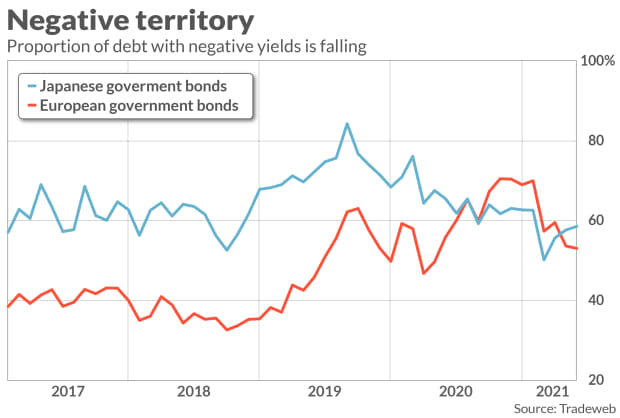

Yields in the eurozone have been on the rise. And investors have noted that the stockpile of global debt sporting negative yields — meaning investors were paying for the privilege of lending money — has started to shrink significantly. The chart below tracks the percentage of European and Japanese government bond yields that remain negative.

According to Bloomberg, the total stockpile of negative-yielding debt around the world has dropped from more than $18 trillion in December to around $13 trillion.

That’s largely good news, as negative yields are associated with dire economic conditions.

The past week saw the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note fall 3.3 basis points, or 0.033 percentage point, to 1.559%, for its lowest 3 p.m. Eastern close since April 21, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

U.S. stocks rallied Friday, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA closing at 34,756.39, logging a weekly rise of 0.7%. The S&P 500 SPX saw a weekly rise of 0.6%, while the Nasdaq Composite COMP gained 0.5%. The Dow and S&P 500 both ended just 0.06% of their record finishes from May 7, according to Dow Jones Market Data.