We’re looking at stocks as money pots, and that’s just not in the cards

If Warren Buffett is right that investors should be fearful when others are greedy, then we should be scared right now. Really scared.

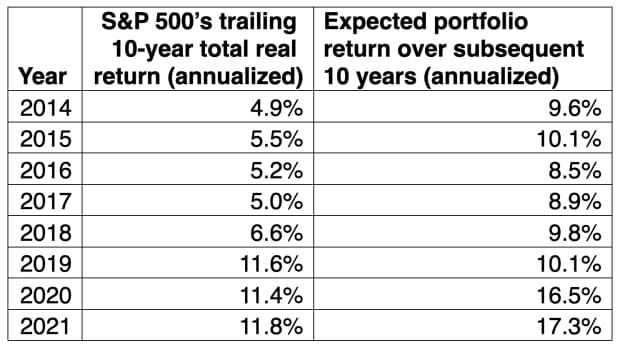

Consider by how much individual investors in the U.S. expect their portfolios to beat inflation in coming years. According to the 2021 Natixis Global Survey of Individual Investors, they on average expect their portfolios to produce an inflation-adjusted return of 17.3% annualized over the next decade. That’s nearly triple the U.S. stock market’s long-term average real total return of 6.1% annualized, and more than four times the bond market’s long-term average total return of 4.1% annualized (since 1793, according to data from Edward McQuarrie of the Leavey School of Business at Santa Clara University).

Given the U.S. stock market’s extreme overvaluation right now, coupled with real interest rates that are negative, a far better bet is that stocks and bonds will each produce returns even lower than these long-term averages in coming years. Yet as is clear in table below, U.S. investors have instead become progressively more bullish. Far from becoming more fearful as the stock market has rewarded greed, investors have become even greedier.

Such behavior is not new. It’s because of it that investors will be their most bullish at market tops. That is precisely when they should be most bearish, and is why Buffett’s advice is so worthwhile.

Few of us actually follow Buffett’s advice for fear of missing out on the bull market’s continuation. You might think that investors’ biggest fear is losing money, but many money managers over the years have told me that this is not the case. More intolerable than losing is not making money as the stock market continues higher. As famed British economist John Maynard Keynes brilliantly put it, we would rather “fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.”

This paradox of human nature was documented in a classic study several decades ago by Sara Solnick, an economics professor at the University of Vermont, and David Hemenway of Harvard University’s School of Public Health. In a survey, faculty, students and staff at the School of Public Health were asked to pick which of two different possible salary schedules they would choose when taking a new job:

- Being paid $50,000 a year when everyone else in the organization is getting paid $25,000

- Being paid $100,000 a year when everyone else is being paid $200,000.

Believe it or not, half the respondents chose the first option — even though it meant that, in absolute terms, they were being paid half as much.

In an interview, Hemenway told me that similar conclusions have been reached in numerous additional studies subsequent to this original study. He added that this phenomenon, referred to as “positionality,” appears to be stronger in some areas than others. Not surprisingly, it’s particularly strong when status is most important.

Hemenway said he hasn’t studied positionality in investing, but it seems clear to me that it’s important. We tend to judge our portfolios according to whether they are ahead or behind the market as a whole — which, of course, represents everyone else. For example, we’re perfectly happy to book a 10% gain when the S&P 500 SPX,

Though it’s easier said than done, we need to reframe how we judge our investment performance, shifting away from comparisons to everyone else and focusing instead on our needs. This is hardly a novel suggestion, even if few actually follow the advice. Benjamin Graham, the father of fundamental analysis, wrote in his book “The Intelligent Investor”: “The best way to measure your investing success is not by whether you’re beating the market, but by whether you’ve put in place a financial plan and a behavioral discipline that are likely to get you where you want to go.”

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at mark@hulbertratings.com

More: These 15 stocks — June’s biggest losers — could become July’s winners

Plus: What the stock market’s ‘black swan’ index hitting an all-time high tells us