Grantham’s terrifying new forecasts

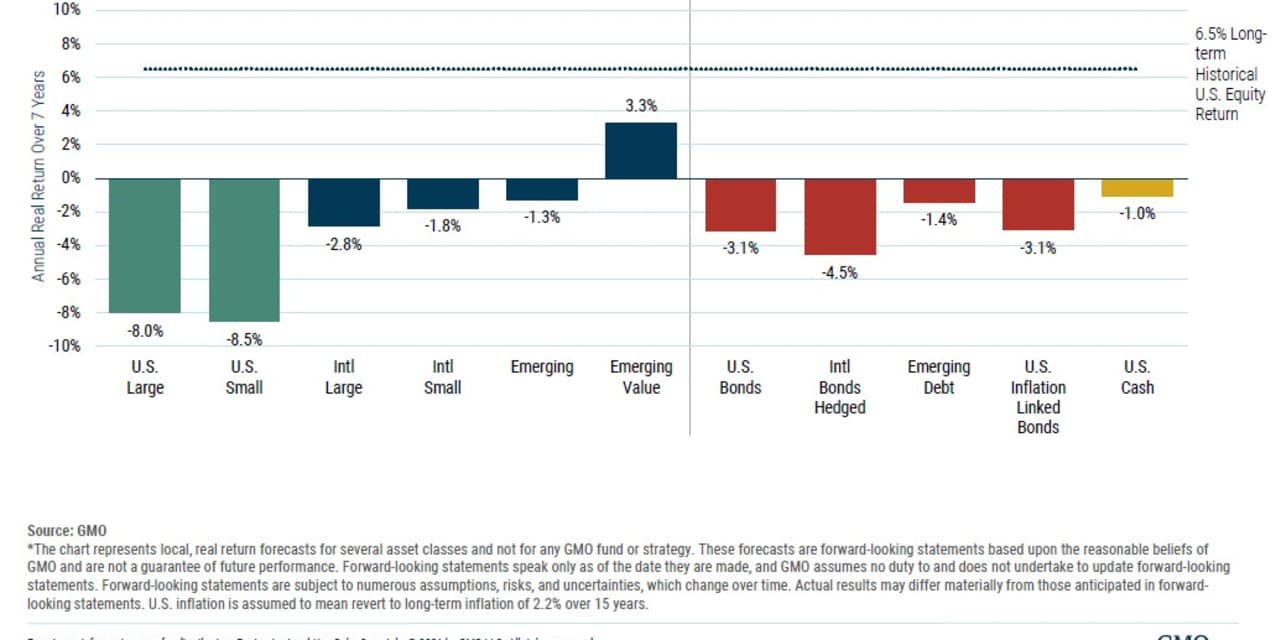

If you have a 401(k) and you’re of a nervous disposition, you probably don’t want to look at the chart above.

Even by the standards of GMO, the super-cautious money management firm in Boston best known for its famous co-founder Jeremy Grantham, it’s terrifying.

It shows about the worst medium-term forecasts on record for pretty much all the assets most of us own in our retirement accounts. Large company U.S. stocks like the S&P 500 SPY,

In the case of some of these mainstream investments, the predicted losses are huge. Those 8% and 8.5% annual losses on U.S. large-caps and small-caps? If they happen, they’ll mean your SPDR S&P 500 ETF SPY,

I’ve been following GMO’s forecasts for nearly 20 years. I’ve never seen one this bad, and I’ve seen some that were really bad—like the ones they made in 2000 and 2007, just before the two big crashes.

There is a tendency at certain moments for market followers to roll their eyes whenever anyone mentions the latest gloomy predictions from GMO. “Those guys have been wrong for years,” say skeptics. They point out, for example, that GMO 10 years ago predicted emerging markets would probably do really well and U.S. stocks badly. Instead, the reverse happened.

Go to an online chat room like Bogleheads and you can find plenty of skeptics.

According to FactSet, the GMO Global Allocation Fund has earned you a total return of just 22% over the past five years. The Vanguard Balanced Index Fund VBINX,

But it’s not quite that simple. GMO was among the few firms to predict the 2000-2003 and 2007-2009 crashes. And each time, people laughed. The online chat rooms were different — 20 years ago it was Yahoo and Raging Bull—but the sound was the same.

In the event, the warnings GMO made in the late 1990s were remarkably accurate. It ranked 10 major asset classes by future investment performance, and got them pretty much in line. “The chances of getting that forecast exactly right were less than one in 500,000,” The Economist magazine calculated.

The worst among the 10? The S&P 500.

I also remember Grantham warning in the summer of 2007, when the markets were booming, that at least one major Wall Street bank would go bust within the next two years. At the time people thought he’d finally gone off the rails. They probably thought that at Bear Stearns (d. 2008) and Lehman Brothers (d. 2008) too.

Oh, and he turned aggressively bullish on stocks during the depths of the 2007-2009 global financial crisis. As he wrote at the time: If stocks are cheap and you don’t buy them and then they go up, you don’t just look like an idiot, you are an idiot.

GMO is currently getting so much flak from people on antisocial media that in an unusual move it has just published a robust defense of its forecasts. I could have told them defending themselves against people on antisocial media is a total waste of time. Twitter, as the WOPR might say, is like Tic-Tac-Toe and Global Thermonuclear War: The only way to win is not to play.

But in an unsigned note from the firm’s asset allocation team—chaired by firm honcho Ben Inker—GMO points out that by some measures the S&P 500 may be even more overvalued today than it was in 1999-2000.

What are we ordinary investors to make of this? History suggests that the time when we most need to listen to people like GMO is precisely the moment when everyone has stopped doing so.

Furthermore, when we dismiss these types of warnings we have to watch out that we’re not double-counting. By definition, the more you pay for stocks, the lower must be your future long-term returns. If the stock market goes through the roof, that suggests we should become more cautious, not less, about what we’ll get down the road.

As a longer-term, retirement plan investor, GMO’s warnings don’t make me want to sell everything. But they do remind me to check my risks. If I couldn’t ride out a 50% fall in the market over the next 5-10 years, I probably own too many stocks. And, most important, they remind me to diversify.

GMO believes there are investments out there that offer much better prospects than the S&P 500: Among them “emerging market value” stocks, meaning cheaper, typically older stocks in developing markets from China to Brazil, small-company stocks in Japan, and more generally value and high-quality stocks everywhere. There are good diversification opportunities for those who are all-in on U.S. stocks alone.

I wouldn’t hang my hat on these forecasts. But I wouldn’t ignore them either.