The Great Resignation is being driven entirely by this one demographic

The so-called Great Resignation has erupted in America’s consciousness, referring to the waves of people leaving the workforce and the difficulty companies are having in finding replacements.

The big question, for financial markets and policymakers alike, is whether these workers are gone for good. Some posit that’s the case, which would lead to permanently higher wages, reduced profits and higher prices for consumers.

Economists at Barclays led by Michael Gapen disagree. They say what’s going on is more of a “Great Hesitation.”

“The high quit rate is a red herring for understanding the sluggish return of workers to the U.S. labor market following the COVID-19 pandemic, in our view. Instead, the true cause is a hesitation of workers to return to the labor force, due to influences tied to the pandemic such as infection risks, infection-related illness, and a lack of affordable childcare,” these economists say.

For one, the quit rate has generally coincided with an uptrend in the hiring rate. “For now, we note that these voluntary job separations have been met with job finding by businesses, hinting that these resigners are more accurately described as switchers,” they say in a new research ntoe.

Another finding, based on the Atlanta Fed’s wage-growth tracker, is the wage growth is led by job switchers — almost entirely in the 16- to 24-year-old cohort — “who are generally less skilled and are less likely to be constrained by non-pecuniary considerations (such as infection risks, childcare, healthcare insurance, and work location) that might otherwise affect their ability to switch jobs.”

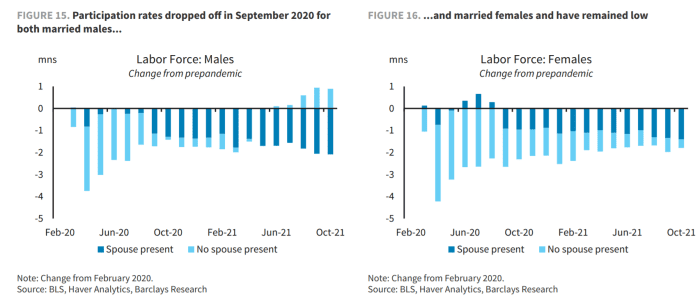

One unique finding in the Barclays report is their demographic analysis of the labor force now as compared to February 2020. Married people living with their spouses more than account for the entire decline in participation. Of the 3 million decline in the labor force compared to February 2020, there were 3.5 million fewer married workers. There was a corresponding half million increase in the participation of workers not living with their spouse.

At the onset of the pandemic, the participation declines were almost entirely among the unmarried, but that changed by September 2020. “We think that this reflects the fact that ‘co-insurance’ from being in a dual-earner household provides greater scope for sidelined spouses to be more circumspect about re-entering the labor market. That makes other considerations, such as infection risks, pandemic-related childcare challenges, and unusually healthy balance sheets more likely to tip the scale against working,” they say.

An examination of occupational position finds declines in the labor force almost entirely concentrated in serivce jobs, sales and non-professional office and administrative positions. “To be sure, these categories have also been hit hard by demand-side pandemic influences, with households redirecting demand from services to goods and with office support-staff sidelined by telework. However, other common threads, in our view, are that these occupations generally require less skill and involve considerable interpersonal interaction, thereby implying higher infection risks,” the economists say.

The Barclays team does expect to see most of the missing workers making their way back to the U.S. force, though gradually. They do point out, for many, retirement is not necessarily a permanent state.

“Given the composition of retirees and nonparticipants, the higher reentry rates for non-retirement age workers, and the unusually high participation rate for near-retirement age workers in the lead-up to the pandemic, our expectation is that flows out of retirement in the coming quarters will be much higher than normal,” they say.