Wall Street is a perpetual battleground for the forces of fear versus greed. But every so often the greed gets out of hand.

That can make the Street a fertile ground for fraud. Some of the most notorious financial crimes of all time have ties to the corner of Wall and Broad, and their impact — on victims, law enforcement, and future would-be crooks — lasts to this day.

Let’s catch up with some of Wall Street’s most audacious fraudsters.

‘Bring it on, baby!’

Information is the coin of the realm in any financial market. A hot stock tip can be a ticket to riches, and some people are willing to break the law to get one.

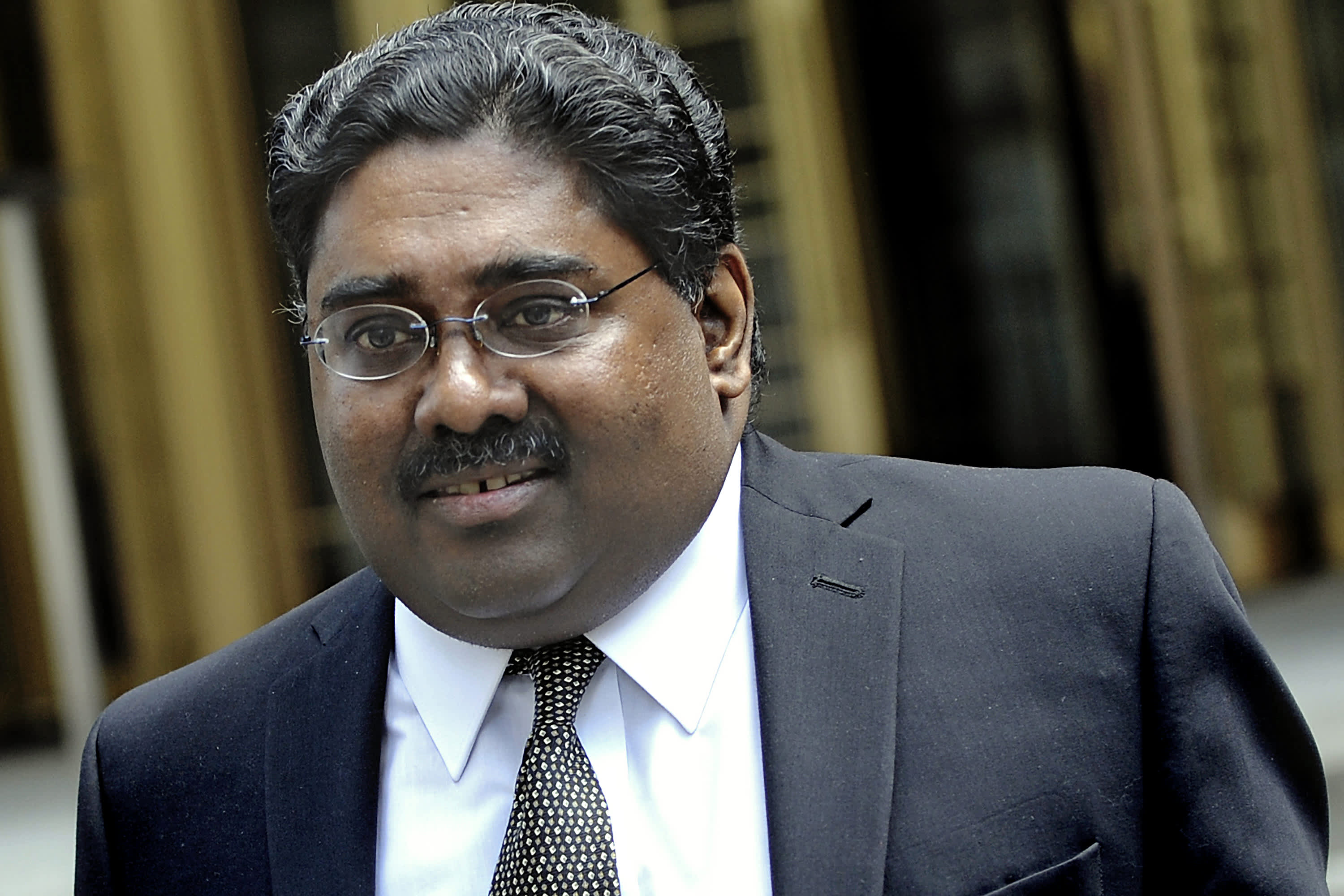

As founder of the Galleon Group, hedge fund manager Raj Rajaratnam had an uncanny ability to beat the market in the area that he and his team of traders and analysts specialized in: technology stocks. Investors were so impressed that they poured enormous sums of money into Galleon, which peaked at $7 billion under management and made Rajaratnam a very wealthy man.

How did Rajaratnam get to be so plugged into the secrets of the tech world? As detailed in a 2012 episode of CNBC’s “American Greed,” he had a secret of his own: a network of corporate insiders who supplied him with material information about their companies before it got out to the public and the stock market. That is illegal under federal insider trading laws.

“I think he felt a sense of power, that he had access to information that no one else had. And that he was able to profit by it,” said former Assistant U.S. Attorney Joshua Klein, now a partner at Petrillo, Klein and Boxer in New York, in an interview with “American Greed.”

The big break in the case came when investigators managed to get a warrant to wiretap Rajaratnam’s phones — a tactic never before employed in an insider trading investigation. Rajaratnam’s defense team fought hard in court to suppress the recorded conversations, but they were unsuccessful.

When prosecutors played the recordings at Rajaratnam’s 2011 criminal trial, it lifted the veil on a corner of Wall Street not previously seen — or heard — by the general public. Rajaratnam could be heard fielding calls from company insiders and even a Goldman Sachs board member supplying him with market-moving information that the public would only learn about later.

In one of the more colorful conversations played in court, Rajaratnam and Danielle Chiesi, a portfolio manager at another firm who would later plead guilty to conspiracy with Rajaratnam, banter about their access to secret information at some of the era’s most important technology companies.

“I must defer to you on IBM,” Rajaratnam concedes.

“And Akamai too?” Chiesi replies.

“Akamai, too,” Rajaratnam says. “But AMD? Bring it on, baby!”

A federal jury in Manhattan convicted Rajaratnam on 14 counts, including conspiracy and securities fraud. A judge sentenced him to 11 years in prison. A federal appeals court upheld the verdict, rejecting an appeal that centered on the wiretaps.

Released from prison into home confinement in 2019, and having completed his sentence in April 2021, Rajaratnam still maintains his innocence. And he accuses then-U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara and his team of unfairly exploiting “murky” insider trading laws.

Rajaratnam has written a book whose title leaves no doubt about where he stands: “Uneven Justice: The Plot to Sink Galleon.”

In his first interview since his 2009 arrest, Rajaratnam told CNBC’s Andrew Ross Sorkin earlier this month that his successes were not the result of illegal insider trading, but legitimate market research.

“We spent maybe 10 or 12 hours a day doing deep research,” he said. “There’s a theory called the Mosaic Theory on Wall Street where you take little dots of information and connect it. And that’s perfectly legal.”

Chiesi, who was sentenced to 30 months and was released from prison in 2013, lists herself on LinkedIn as a “military philanthropist” who helps servicewomen transition back to civilian life.

‘Mad Max’ of Wall Street

Years before Rajaratnam’s trades took Wall Street by storm, California stock trader Amr Ibrahim “Anthony” Elgindy was making money on a different sort of information. He claimed he had the unique ability to spot fraudulent companies and call out their chicanery, thereby reforming the markets. Time and again, stocks that he targeted plunged on word some sort of government investigation or trading halt, which Elgindy could claim he predicted.

Elgindy’s rapid-fire, ostentatious style, along with his promise to blow the lid off of crooked companies, earned him the nickname “Mad Max of Wall Street,” profiled in a 2010 episode of “American Greed.”

Eager to go along for the ride in the wild, day-trading era of the late 1990s and early 2000s, market players paid as much as $600 per month for access to his subscription-based web site, newsletters and chat rooms. There, they could get the first word on so-called “fraud alerts” issued by Elgindy — who went by the online moniker Anthony@Pacific — and join him in shorting the stocks, betting they would go down. When the stocks did indeed plunge — sometimes all the way to zero—Elgindy and his followers made a fortune.

But there were a few things his subscribers didn’t know about.

Elgindy was able to spot so many companies just before they found themselves on the wrong side of the law not because of canny financial analysis, but because of a crooked FBI agent, Jeffrey Royer.

At first, according to their 2002 federal indictment, Elgindy would alert Royer about companies that he deemed suspicious, and Royer would dutifully start asking questions in his official capacity. Word of an FBI investigation was poison to a stock — especially a small cap, thinly traded one. So, when that word got back to Elgindy’s followers and the rest of the market, as it inevitably did because Elgindy and his subscribers would trumpet it, their short-selling bets paid off.

Soon, according to the indictment, Royer took the operation a step further by tapping into secret FBI databases to learn about real investigations that were underway. Then, he tipped off Elgindy, and the short-selling frenzy went into overdrive. But even that wasn’t enough for the Mad Max of Wall Street.

Prosecutors said that often, once a targeted company’s stock had become nearly worthless, Elgindy would extort company insiders to sell or give him shares of the cheap stock in exchange for calling off his short-selling followers. That way, he could make money on the stocks again on the way back up — a reverse version of the classic Wall Street pump-and-dump scam.

In 2005, a federal jury in Brooklyn convicted Elgindy and Royer on multiple felony counts, including racketeering conspiracy and securities fraud.

Elgindy was sentenced to eleven years in prison and was released in 2013. He died in 2015 at age 47. Royer was sentenced to six years in prison and was released in 2012 according to U.S. Bureau of Prisons records.

A ‘wolf’ in stockbroker’s clothing

When it comes to the excesses that give Wall Street a bad name — the money, the parties, the drugs, you name it — there are few parallels to Jordan Belfort. He is the self-proclaimed “Wolf of Wall Street,” who wrote about his debauchery in a 2007 book of the same name. Filmmaker Martin Scorsese turned it into a hit movie in 2013 with Leonardo DiCaprio playing Belfort in an Oscar-nominated turn.

“The word on Wall Street was that I had an unadulterated death wish and that I was certain to put myself in the grave before I turned thirty. But that was nonsense, I knew, because I had just turned thirty-one and was alive and kicking,” Belfort wrote.

Jordan Belfort

Jono Searle | Newspix | Getty Images

Not content to work his way up the ladder on 1980s Wall Street, Belfort founded Stratton Oakmont, a bucket shop on Long Island that turned the pump-and-dump scam into practically an artform.

Belfort and his team of young guns specialized in what were then known as over-the-counter stocks, companies too small to be listed on the major exchanges and small enough to escape most regulatory scrutiny. The Stratton Oakmont sales force relentlessly pushed the stocks on investors, driving up the prices to unsustainable heights before selling their shares and pocketing the investors’ money as the price plunged, laughing and partying all the way to the bank.

In 1999, Belfort pleaded guilty to 10 felony counts including conspiracy, market manipulation and money laundering, and he served 22 months in prison.

These days, he is still making money off of his wolfy past, offering online courses on sales and persuasion— the full course selling for $3,999, which his web site advertises as a “50% discount.” He also offers seminars and paid speeches, billing himself as an “investment guru,” the “world’s number one sales trainer,” and an “entrepreneurship expert.”

And he is happy to hold forth in the media on the pressing financial topics of the day, including Bitcoin, which he predicted on CNBC would “go bust within a year” — in 2018.

Belfort’s Stratton Oakmont customers have said they are still being victimized. Several spoke with “American Greed” in 2015, soon after the home video release of “The Wolf of Wall Street,” a film that barely mentions the people who were hurt.

“Too many people walk out of a movie and think they have seen the story, and it leaves out significant parts of the story, not the least of which is 15-hundred people that lost real money,” said Bob Shearin of California, who said he lost $130,000.

Court records show Belfort has repeatedly resisted efforts to force him to pay more of the $110 million he was ordered to return to his victims. In 2018, a federal judge ordered him to turn over his entire stake in a wellness company after documents showed he had only paid $12.8 million in restitution.

In one of the craziest twists in an already crazy story, Belfort sued a production company behind “The Wolf of Wall Street,” Red Granite Pictures, for $300 million in 2020, after the studio’s co-founder became ensnared in a Malaysian money laundering scandal. Belfort accused the studio executive of “tainting” his story, an ironic claim by an admitted fraudster. The studio said in a court filing that Belfort’s suit was “as morally bankrupt as he is.”

Months later, Belfort agreed to drop the suit and submit his claims to arbitration, where any settlement would be confidential.

All the greed that’s fit to print

Sometimes, the best way to get an edge in the stock market is to go behind the headlines. David Pajcin and his friend Eugene Plotkin took that concept literally in 2004 and 2005, in a story told in a 2009 “American Greed” episode.

In the early 2000s, the “Inside Wall Street” column in BusinessWeek Magazine was enormously influential. Back then, the print editions of financial publications still mattered, even as the internet was taking hold. Serious investors waited each week for their copy of the magazine and their chance to pounce on whatever stock the column was talking about that week.

Wouldn’t it be great, Pajcin and Plotkin mused, if they could see the week’s column before everyone else did? This would be much easier said than done, since BusinessWeek’s publisher at the time, McGraw-Hill, employed strict security procedures to make sure the contents of “Inside Wall Street” did not get out until precisely 5:00 p.m. on Thursdays, after the market closed.

The process, in which only a handful people knew what was in the column before the magazine went out, worked well but for a single flaw: greed.

According to court filings, Pajcin and Plotkin paid two employees at the company that printed BusinessWeek to give them advance word of what was in the column so they could trade the stocks. They were able to get ahead of the market in 20 stocks over a nine-month period in 2004 and 2005, prosecutors said. But the scheme did not end there.

Pajcin and Plotkin also found a crooked insider in the mergers and acquisitions department at Merrill Lynch who tipped them off about upcoming deals. And a grand juror in an investigation of a pharmaceutical company CEO tipped them off that the executive was about to be indicted.

The operation finally collapsed when U.S. authorities traced some $2 million in trading proceeds to the account of a retired underwear seamstress in Croatia named Sonja Anticevic, who happened to be David Pajcin’s aunt.

In all, six people pleaded guilty to criminal charges in an operation that netted more than $7 million. Pajcin, who was first to flip, was sentenced to time served and released in 2008. Plotkin got nearly five years and was released in 2011.

Thirteen people were ordered to pay civil penalties to the Securities and Exchange Commission, including Aunt Sonja the seamstress — proving that even the most ingenious insider trading schemes are often full of holes.

Meet more of the world’s most brazen thieves on the ALL-NEW season premiere of CNBC’s longest-running prime time original series, “American Greed,” on a new night — Wednesday, January 5 at 10 p.m. ET. In 15 jaw-dropping seasons and 200 episodes, the truth remains: some people will do anything for money.