Stocks are rallying because of what an inverted yield curve says about the Fed and inflation, strategist says

The inversion of a key measure of the Treasury yield curve is telling investors more about inflation and the Federal Reserve’s credibility than it is about the prospect of recession, according to a veteran Wall Street strategist.

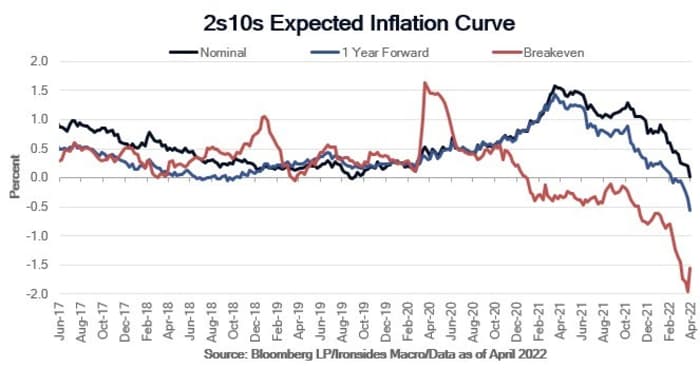

“The inversion of the 2s10s nominal Treasury curve is not implying slower growth, but rather lower inflation in 2023 and beyond,” wrote Barry Knapp, managing partner of Ironsides Economics, in a Sunday note.

Knapp was referring to moves along the yield curve — a line that measures yields across all Treasury maturities. Last week, the yield on the 2-year Treasury note TMUBMUSD02Y,

Knapp argued that growth signals from the yield curve have been largely disabled since the early 2000s amid waves of global central bank intervention that has distorted the level and direction of long-dated Treasury yields.

The current inversion of the 2-year/10-year yield curve, he has argued, has likely been driven by a deep inversion of what’s known as the break-even curve, which indicate market expectations for future inflation (see chart below).

Knapp said his counterintuitive take, if correct, explains the sharp rally by the stock market since the Fed’s March 15-16 policy meeting, when the central bank lifted rates by a quarter of a percentage point, signaled a series of sharp rate increases were to come and indicated that a plan to unwind its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet could come as soon as its next meeting in early May.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA,

The equity bounce, he said, would be “consistent with our analysis of the hawkish Fed pivot and incremental increase in credibility.”

Read: Why an inverted yield curve is a bad tool for timing the stock market

Much of the focus around the yield curve has indeed been centered on the idea that the Fed’s aggressive response to inflation running at its hottest in four decades would eventually put the economy in the ditch. In other words, if inflation was on track to be tamed, it would come at with the cost of a recession.

Investors, analysts and economists, meanwhile, continue to debate the meaning of the 2-year/10-year yield-curve inversion. Such inversions have preceded all six recessions since 1978, with just one false positive, economists said. But the 3-month/10-year spread is seen as even, if only slightly, more reliable and has been more popular among academics, noted researchers at the San Francisco Fed. That curve remains far from inverted, with the 10-year yield more than 1.8 percentage points above the 3-month yield.

Stocks, meanwhile, have tended to perform well long after a 2-year/10-year inversion, with a peak for the S&P 500 coming a median 18 months after such a flip, according to Invesco, which cited data going back to 1965.