Inflation may be a lot lower than anyone thinks — even the Fed

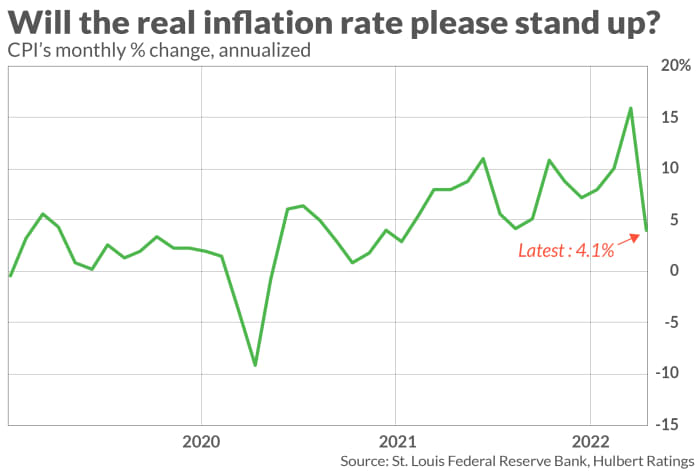

U.S. inflation in April plunged to an annualized rate of 4.1% — less than half of where it stood in the prior month.

This will no doubt come as a surprise for those of you who focus only on the financial headlines. They informed us that the Consumer Price Index dipped slightly in April, to 8.3% from 8.5%. This modest decline was less than what Wall Street had been expecting, and on the day it was reported the S&P 500 SPX,

But the headline CPI number focuses on its 12-month rate of change. If you focus on the monthly rate of change, as shown in the chart below, then it becomes readily apparent how much inflation dropped from March to April.

The CPI’s 12-month rate of change is inflated by big jumps in June and October of 2021 and March of this year. As a result, the 12-month rate of change will remain high regardless of what happens to the CPI over the next couple of months. One illustration of this: even if the CPI had remained unchanged from March to April, the headline number for April would still have been 7.9%.

This puts the current discussion about inflation in an entirely different light. The month-to-month inflation rate doesn’t have to get any lower than it was in April in order for the CPI’s 12-month rate of change to fall to 4.1% — once the past year’s big spikes in inflation drop out of the trailing 12-month period.

Until those spikes drop out of the calculation, the headline inflation number will remain stubbornly high — not because the Federal Reserve is doing a bad job fighting inflation but because of simple arithmetic.

Alan Reynolds, an economist who is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute and former vice president of the First National Bank of Chicago, recently put it well: “The Fed… cannot possibly do anything to quickly reduce year‐to‐year CPI headline inflation because most months included in that statistic are now behind us.”

Was April’s inflation rate the exception or the rule?

This relatively sanguine assessment of current inflation assumes that the CPI’s percentage change in April persists in coming months. That would not be a good assumption if the April rate was artificially low.

Some have indeed worried this was the case, including my MarketWatch colleague Rex Nutting in a recent column. For example, while gasoline prices — which are a big component of the CPI — were lower in April than in March, they have since rebounded and are now even higher than they were in March.

The broader point of this discussion, though, is that we need to be focusing on the future rather than the past. Yet by focusing on the CPI’s 12-month rate of change, most investors are guilty of what behavioral economists refer to as the “base rate fallacy:” They are overlooking the extent to which the CPI’s 12-month rate of change is being biased by an abnormally low CPI level 12 months ago.

You may still argue that inflation will remain stubbornly high for a long time, of course. Just don’t base your argument on the lingering effects of the CPI’s few big monthly jumps over the past year.

Mark Hulbert is a regular contributor to MarketWatch. His Hulbert Ratings tracks investment newsletters that pay a flat fee to be audited. He can be reached at [email protected]