DUBAI, United Arab Emirates — In what now feels like a familiar story, Israel’s government has collapsed after the Parliament, or Knesset, voted on Thursday to dissolved itself.

This paves the way for a fifth election in three years, after the most diverse and unlikely coalition in the country’s history — which featured centrists, right wingers, left wingers, and even Islamists — eventually hit a level of gridlock it could not overcome, just one year into its existence.

Prior to that coalition’s formation, Israel went through four elections in the space of two years, each one inconclusive enough to force another vote. Israel’s last government formation process almost exactly one year ago saw Benjamin Netanyahu, the country’s longest-serving prime minister, removed from office after 12 years.

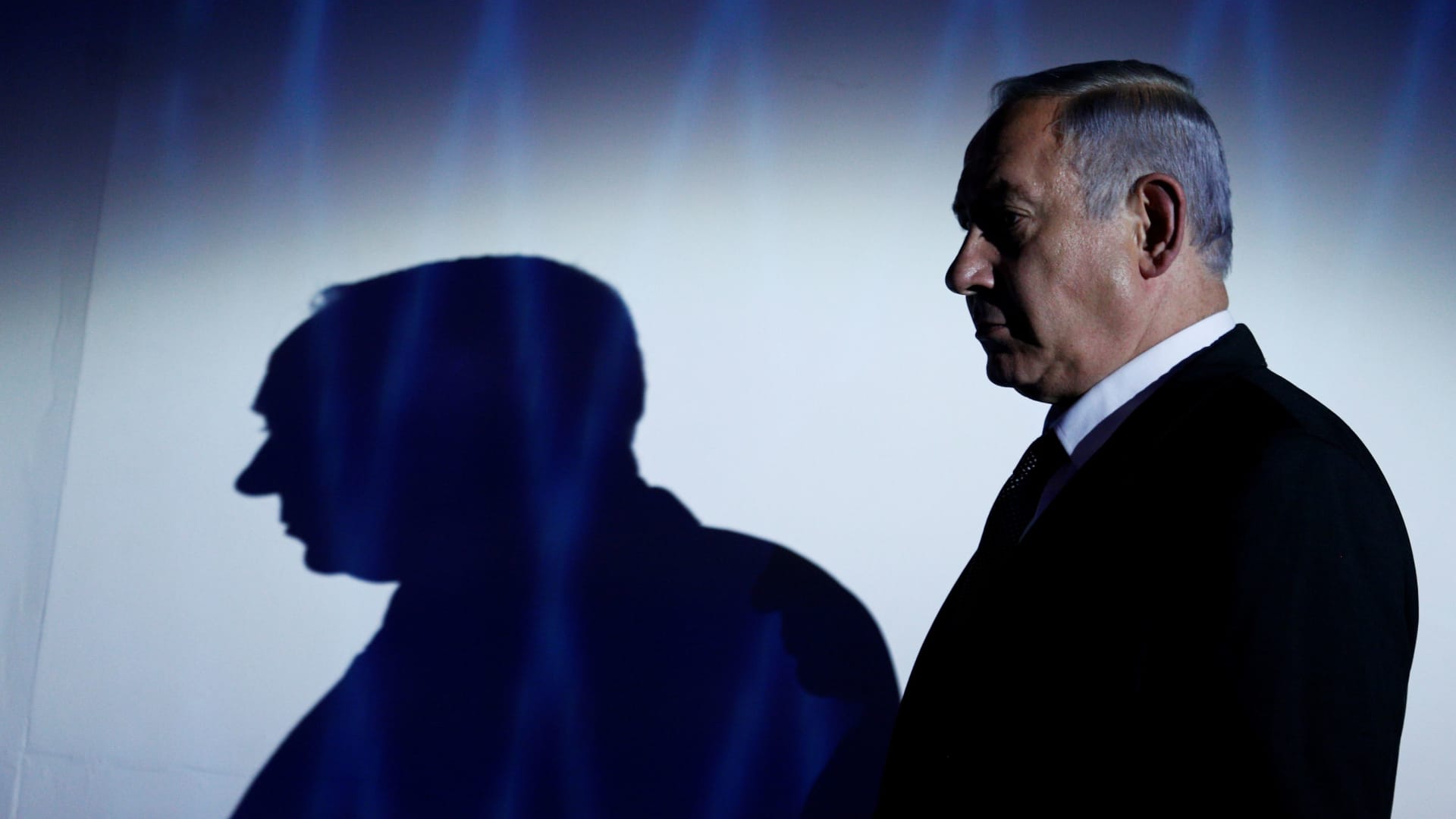

Israel’s current predicament reflects the increasing polarization in the Middle Eastern country of over 9 million, some observers say, as well as acutely different views on the country’s direction. But it also offers a potential second chance to the controversial Netanyahu, whose right-wing Likud party is performing well in local polls. Elections will be held in the fall.

“We did everything we possibly could to preserve this government, whose survival we see as a national interest,” Israel’s Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, a far-right wing former settler leader, said in a speech last week.

“To my regret, our efforts did not succeed.”

Another chance for Bibi?

Netanyahu didn’t feel so sad.

“This evening is wonderful news for the citizens of Israel. This government has ended its path,” the former prime minister said after the initial news was announced on June 21, detailing a list of criticisms of the outgoing coalition. “This government is going home.”

The 72-year-old Netanyahu is a lightning rod in Israeli politics, often described as an “either you love him or you hate him” figure. He drew the ire of many of his own party members last year when he refused to step down despite being under investigation for a number of corruption charges. His trial is underway and could last several years — and there is no law on the books that prevents him from becoming prime minister again despite the charges.

“Netanyahu’s return is by no means inevitable — it’s still early — but if his political career has shown anything over the years, it’s that it’s best not to underestimate him,” Aaron David Miller, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wrote in a commentary for the think tank.

“Netanyahu wants the job more than any other Israeli politician and is prepared to say and do just about anything to attain it,” Miller wrote, adding that more than just politically, this is a matter of personal survival for the current Likud party leader.

“Being prime minister is the only way he can manipulate the system to get his indictment overturned through some legislative chicanery,” he wrote.

The election’s outcome, while likely to maintain the status quo in terms of support to businesses and Israel’s booming tech sector, will determine future relations with Palestinians and Arab states, the Biden administration, dealing with record-high inflation, and the country’s security.

Assessing the competition

In order to lead the government in Israel, a party has to win a majority of 61 seats — the magic number — in Parliament. If that isn’t attainable, the party with the most seats has to negotiate alliances with other parties to form a coalition.

This often results in very unlikely bedfellows, as evidenced in Israel’s latest government. While the coalition did manage to pass an important budget and improve its relationship with the Biden administration, it hit a wall when it came to Israeli-Palestinian affairs, against the backdrop of increasing violence between Israelis and Palestinians.

The public debate is going in the same direction as it did in previous elections, said Assaf Shapira, director of the Political Reform Program at Jerusalem-based think tank the Israel Democracy Institute.

The main determinant of how people vote will be “Netanyahu or not Netanyahu,” Shapira told CNBC. “This raises questions about the nature of democratic values in Israel,” he said, adding that “Netanyahu wants to weaken law enforcement” to protect himself from criminal charges. He has also been accused of fanning anti-Arab hatred.

If Netanyahu’s Likud party, currently the biggest in the Knesset, fails to reach the 61-seat majority, he will have to ally with other parties to clinch that number. But just as in June of 2021, a range of parties are bent on opposing him — even right-wing ones. Some party leaders say they would only ally with Likud if Netanyahu stepped down. But so far, no one in his party has provided a clear alternative for leader.

His most formidable opponent for the leadership so far is Yair Lapid, a centrist and former TV presenter who served as foreign minister in the outgoing hodge-podge coalition led by right-winger Bennett.

Lapid’s Yesh Atid party “has survived where most centrist parties don’t,” the Carnegie Endowment’s Miller wrote. Still, he added, “Lapid will face the same set of constraints as Bennett: how to put together and sustain a coalition composed of as many as seven or eight parties whose common objectives don’t go much beyond keeping Netanyahu away” from power.

Lapid’s biggest selling point, Miller added, “is that he engineered a government that beat Netanyahu.” He will now have to convince Israelis that he can effectively lead a divided country, too.

Endless elections

An important event to watch will be President Joe Biden’s visit to the Middle East in July, where he is slated to visit Israel.

The Biden team was not particularly fond of Netanyahu, who went against the Obama administration in past years to expand Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories. While the White House has made clear that it will work with whatever government is elected, Biden will likely attempt to boost Lapid’s image during his visit, Washington-based analysts say.

To be sure, one cannot assume the outcome will be either a Netanyahu or Lapid-led government. As with the last three years, and a very divided voter base, Israel could simply continue falling into more tricky coalition governments, more leadership collapses and more elections.

Specifically for Netanyahu, he is so divisive that a win for him may just mean a repeat of the cycle, Shapira said.

“There are very few alternative leaders within the Likud challenging Netanyahu publicly,” he said. “If it’s still Netanyahu, there are good chances for another election, and another election.”