Imagine a farmer with thousands of acres of land able to pinpoint the beginning of a problem before it spreads across potentially hundreds of acres of crops — all from an image on a computer screen.

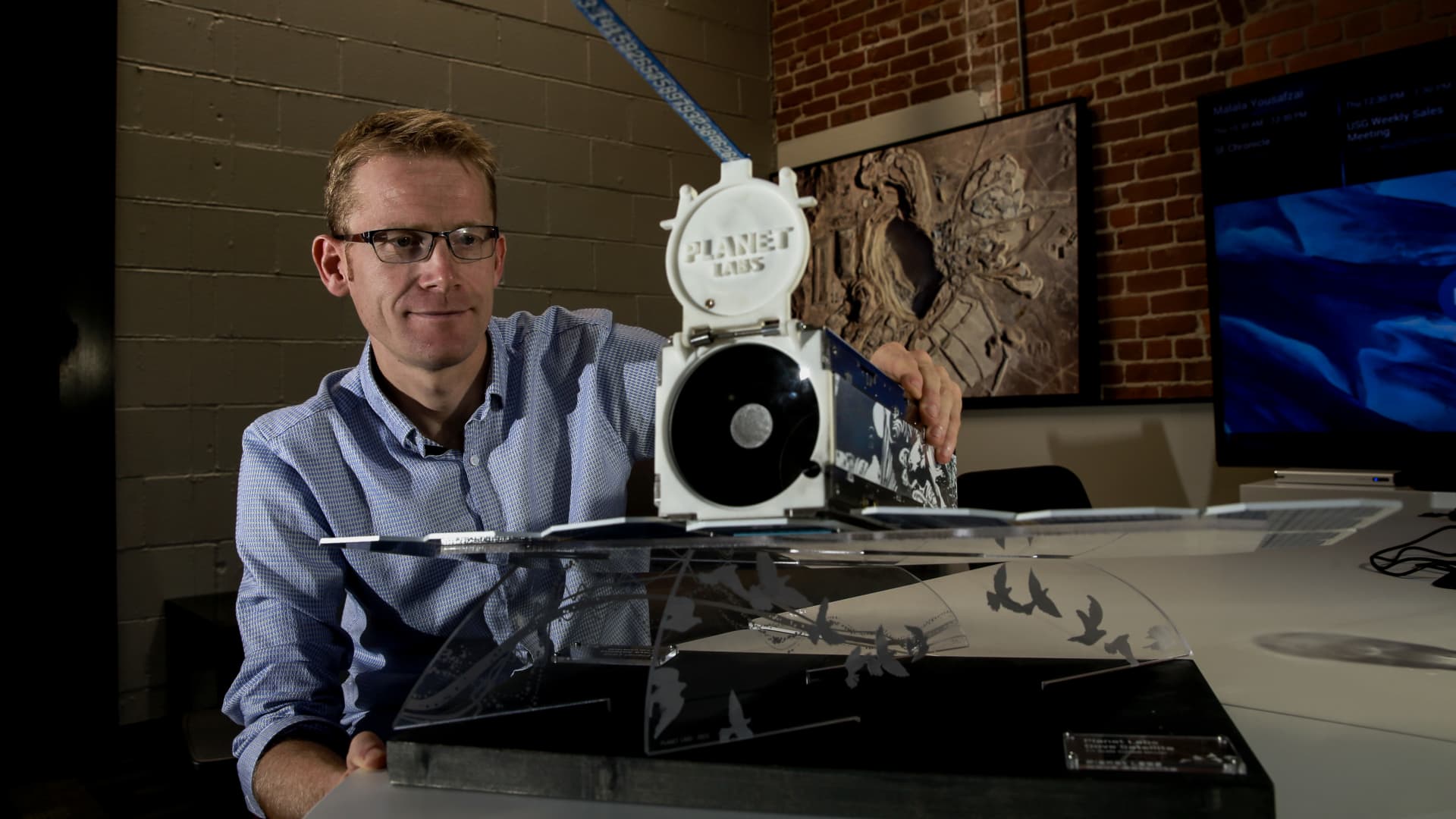

That’s the kind of real-time data that Planet Labs provides. The company, founded in 2010 by two former NASA scientists, launches shoebox-size satellites into orbit that are able to image Earth every day, sending back real-time data on global change. Most of the 200 satellites it currently has operating were sent up on SpaceX rockets, and last year Planet signed an agreement with Elon Musk’s company to be its “go-to-launch” provider through 2025.

Before Planet, most satellites orbiting the Earth were massive, with lead times for images as long as eight years, explains company president Kevin Weil, who spoke at a CNBC Technology Executive Council Town Hall last month. Planet’s founders, Will Marshall and Robbie Schingler, who were working in NASA’s small spacecraft office when they came up with the idea for the company, figured there had to be a quicker, more efficient way to capture images of what was happening on Earth. They believed that smaller satellites, using essentially off-the-shelf parts, could be launched and iterated much more rapidly, much in the same way software is upgraded.

To prove it, Weil said they strapped a solar cell onto the back of an Android phone and launched it into space. “They found it could operate in space, take pictures of the earth and could even, using its radio, send those pictures back down to a ground station on earth,” Weil said. From that test, Marshall and Schingler set out to build satellites the size of a shoebox, each weighing around 12 pounds.

Governments, NGOs, and commercial companies are now some of Planet Labs’ customers, which also include nearly all of the biggest agricultural companies. This latter group, Weil explains, uses the tech to help farmers through Planet’s images by monitoring global crop yields and helping to alert them to problems that they can’t easily see from the ground.

Providing ground truth

Before Planet, Weil said farmers would have to walk around a field to determine how crops were developing, which ones were growing faster (or slower) than others, and how harvesting schedules might need to be changed. A farmer with thousands of acres of fields can’t walk every one each day, so problems were often missed until they became obvious and costly.

Now, a fleet of Planet’s satellites orbiting 500 kilometers above the Earth can monitor every field, every day. When those images are combined with artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, Weil said Planet can provide farmers real-time data that helps address growing issues — sometimes even before they happen. “The data is ground truth and it gives farmers and agricultural companies much more precise monitoring,” he said.

The company sends about 30 to 40 new satellites into orbit each year. Every new one, Weil said, is improved and upgraded based on more sophisticated technology and input from what customers need and want. For example, a recent iteration improved the ability of Planet’s maritime customers to have better resolution of images of water near ports.

Customers pay for Planet’s images based on the size of the area they want to monitor. “People think of us as a satellite company, but we’re really a data company. It’s a recurring revenue SaaS [software as a service] business,” Weil said. Customers sign on for yearly or multi-year contracts since they’re paying to see change over time.

Helping in Ukraine

In Ukraine, Planet’s real-time satellite images are helping the government, NGOs, and other allies manage the food crisis that is developing. Weil said the company’s data shows what crops are being planted, how they’re growing, and what the yield is likely to be. It’s also been able to document evidence of the Russian army stealing wheat and destroying grain silos. “We’re able to document war crimes, but we’re also providing real-time data on the food crisis,” he said. “The more advanced notice of what the wheat deficit is going to be, the better action other countries can take.”

As he looks forward, Weil said he’s particularly excited about a collaboration the company has with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to build what’s called a hyperspectral satellite. Rather than being able to view the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that humans can see, these new satellites will go well into the infrared part of the spectrum and beyond, and have the ability to measure methane and carbon dioxide. For example, Weil said this can help detect gas leaks in pipelines well before they’re noticed otherwise.

“Methane and carbon dioxide emissions are not something we measure well and certainly not on an ongoing basis,” he said. “But these satellites will enable that and help us to measure these emissions. And you can’t manage what you can’t measure.”