Many young people shouldn’t save for retirement, says research based on a Nobel Prize-winning theory

Most financial planners advise young people to start saving early — and often — for retirement so they can take advantage of the so-called eighth wonder of the world – the power of compound interest.

And many advisers routinely urge those entering the workforce to contribute to their 401(k), especially when their employer is matching some portion of the amount the worker is contributing. The matching contribution is – essentially – free money.

New research, however, indicates that many young people should not save for retirement.

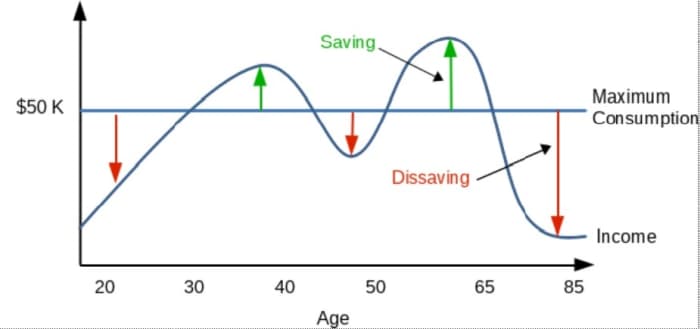

The reason has to do with something called the life-cycle model, which suggests that rational individuals allocate resources over their lifetimes with the aim of avoiding sharp changes in their standard of living.

Put another way, individuals, according to the model which dates back to economists Franco Modigliani, a Nobel Prize winner, and Richard Brumberg in the early 1950s, seek to smooth what economists call their consumption, or what normal people call their spending.

According to the model, young workers with low income dissave; middle-aged workers save a lot; and retirees spend down their savings.

The just-published research examines the life-cycle model even further by looking at high- and low-income workers, as well as whether young workers should be automatically enrolled in 401(k) plans. What the researchers found is this:

1. High-income workers tend to experience wage growth over their careers. And that’s the primary reason why they should wait to save. “For these workers, maintaining as steady a standard of living as possible therefore requires spending all income while young and only starting to save for retirement during middle age,” wrote Jason Scott, the managing director of J.S. Retirement Consulting; John Shoven, an economics professor at Stanford University; Sita Slavov, a public policy professor at George Mason University; and John Watson, a lecturer in management at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

2. Low-income workers, whose wage profiles tend to be flatter, receive high Social Security replacement rates, making optimal saving rates very low.

Middle-aged workers will need to save more later

In an interview, Scott discussed what some might view as a contrary-to-conventional wisdom approach to saving for retirement.

Why does one save for retirement? In essence, Scott said, it’s because you want to have the same standard of living when you’re not working as you did while you were working.

“The economic model would suggest ‘Hey, it’s not smart to live really high in the years when you’re working and really low when you’re retired,’” he said. “And so, you try to smooth that out. You want to save when you have relatively high income to support yourself when you have relatively low income. That’s really the core of the life-cycle model.”

But why would you spend all your income when you’re young and not save?

“In the life-cycle model, we are assuming you are getting the absolute most happiness you can out of income each year,” said Scott. “In other words, you are doing your best at age 25 with $25,000, and there is no way to live ‘cheaply’ and do better,” he said. “We also assume a given amount of money is more valuable to you when you are poor compared to when you are wealthy.” (Meaning $1,000 means a lot more at 25 than at 45.)

Scott also said that young workers might also consider securing a mortgage to buy a house rather than save for retirement. The reasons? You’re borrowing against future earnings to help that consumption, plus, you’re building equity that could be used to fund future consumption, he said.

Are young workers squandering the advantage of time?

Many institutions and advisers recommend just the opposite of what the life-cycle model suggests. They recommend that workers should have a certain amount of their salary salted away for retirement at certain ages in order to fund their desired standard of living in retirement. T. Rowe Price, for instance, suggests that a 30-year-old should have half their salary saved for retirement; a 40-year-old should have 1.5 times to 2 times their salary saved; a 50-year-old should have 3 times to 5.5 times their salary saved; and a 65-year-old should have 7 times to 13.5 times their salary saved.

Scott doesn’t disagree that workers should have savings benchmarks as a multiple of income. But he said a high-income worker who waits until middle age to save for retirement can easily reach the later-age benchmarks. “Savings for retirement probably is more in the zero range until 35 or so,” Scott said. “And then it is probably faster after that because you want to accumulate the same amount.”

Plus, he noted, the home equity a worker has could count toward the savings benchmark as well.

So, what about all the experts who say young people are best positioned to save because they have such a long timeline? Aren’t young workers just squandering that advantage?

Not necessarily, said Scott.

“First: saving earns interest, so you have more in the future,” he said. “However, in economics, we assume that people prefer money today compared to money in the future. Sometimes this is called a time discount. These effects offset each other, so it depends on the situation as to which is more significant. Given interest rates are so low, we generally think time discounts exceed interest rates.”

And second, Scott said, “early saving could have a benefit from the power of compounding, but the power of compounding is certainly irrelevant when after-inflation interest rates are 0% – as they have been for years.”

In essence, Scott said, the current environment makes a front-loaded lifetime spending profile optimal.

Low-income workers don’t need to save either

As for those with low income, say in the 25th percentile, Scott said it’s less about the “income ramp that really moves saving” and more that Social Security is extremely progressive; it replaces a large percentage of one’s preretirement income. “The natural need to save is not there when Social Security replaces 70, 80, 90% (of one’s preretirement income),” he said.

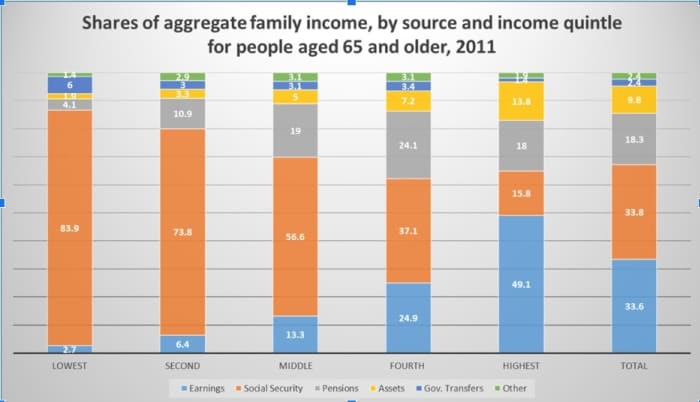

In essence, the more Social Security replaces of your preretirement income, the less you’ll need to save. The Social Security Administration and others are currently researching what percent of preretirement income Social Security replaces by income quintile, but previously published research from 2014 shows that Social Security represented nearly 84% of the lowest income quintile’s family income in retirement while it only represented about 16% of the highest income quintile’s family income in retirement.

Is it worth auto-enrolling young workers in a 401(k) plan?

Scott and his co-authors also show that the “welfare costs” of automatically enrolling younger workers in defined-contribution plans—if they are passive savers who do not opt-out immediately—can be substantial, even with employer matching. “If saving is suboptimal, saving by default creates welfare costs; you’re doing the wrong thing for this population,” he said.

Welfare costs, according to Scott, are the costs of taking an action compared to the best possible action. “For example, suppose you wanted to go to restaurant A, but you were forced to go to restaurant B,” he said. “You would have suffered a welfare loss.”

In fact, Scott said young workers who are automatically enrolled into their 401(k) might consider when they’re in their early 30s taking the money out of their retirement plan, paying whatever penalty and taxes they might incur, and use the money to improve their standard of living.

“It’s optimal for them to take the money and use it to improve their spending,” said Scott. “It would be better if there weren’t penalties.”

Why is this so? “If I didn’t understand that I was being defaulted into a 401(k) plan, and I didn’t want to save, then I suffered a welfare loss,” said Scott. “We assume people figure out after five years that they were defaulted. At that point, they want their money out of the 401(k), and they are optimally willing to pay the 10% penalty to get their money out.”

Scott and his colleagues assessed welfare costs by figuring out how much they have to compensate young workers at that five-year point so that they are OK with having been inappropriately forced to save. Of course, the welfare costs would be lower if they didn’t have to pay the penalty to cash out their 401(k).

And what about workers who are automatically enrolled in a 401(k)? Are they not creating a savings habit?

Not necessarily. “The person who is confused and defaulted doesn’t really know it’s happening,” said Scott. “Maybe they’re getting a savings habit. They’re certainly living without the money.”

Scott also addressed the notion of giving up free money – the employer match — by not saving for retirement in an employer-sponsored retirement plan. For young workers, he said the match isn’t enough to overcome the cost of, say, five years of below-optimal spending. “If you think it’s for retirement, the match-improved benefit in retirement doesn’t overcome the cost of losing money when you’re poor,” said Scott. “I’m simply noting that if you are not consciously making the choice to save, it is hard to argue you are making a saving habit. You did figure out how to live on less, but in this case, you did not want to, nor do you intend to continue saving.”

The research raises questions and risks that must be addressed

There are plenty of questions the research raises. For instance, many experts say it’s a good idea to get in the habit of saving, to pay yourself first. Scott doesn’t disagree. For instance, a person might save to build an emergency fund or a down payment on a house.

As for the folks who might say you’re losing the power of compounding, Scott had this to say: “I think the power of compounding is challenged when real interest rates are 0%.” Of course, one could earn more than 0% real interest but that would mean taking on additional risk.

“The principle is about, ‘Should you save when you are relatively poor so you can have more when you are relatively rich?’ The life-cycle model says, ‘No way.’ This is independent of how you invest money between time periods,” Scott said. “For investing, our model does look at riskless interest rates. We argue that investment expected returns and risks are in equilibrium, so the core result is unlikely to change by introducing risky investments. However, it is definitely a limitation of our approach.”

Scott agreed there are risks to be acknowledged, as well. It’s possible, for instance, that Social Security, because of cuts to benefits, might not replace a low-income worker’s preretirement salary as much as it does now. And it’s possible that a worker might not experience high wage growth. What about people having to buy into the life-cycle model?

“You don’t have to buy into all of it,” said Scott. “You have to buy into this notion: You want to save when you’re relatively rich in order to spend when you’re relatively poor.”

So, isn’t this a big assumption to make about people’s career/pay trajectory?

“We consider relatively rich wage profiles and relatively poor wage profiles,” said Scott. “Both suggest young people should not save for retirement. I think the vast majority of median wage or higher workers experience a wage increase over their first 20 years of working. However, there is certainly risk in wages. I think you could rightly argue that young people might want to save some as a precaution against unexpected wage declines. However, this would not be saving for retirement.”

So, should you wait to save for retirement until you’re in your mid-30s? Well, if you subscribe to the life-cycle model, sure, why not? But if you subscribe to conventional wisdom, know that consumption might be lower in your younger years than it needs to be.